What To Do if You Find Baby Wildlife

Share

Rising temperatures and longer days mean spring is here and summer is on the way. While you’re out for walks, there’s a good chance you could see some newborn wildlife as they learn to navigate this big world.

Case in point: Some adorable bobcat kittens explored a patio in Cave Creek, Arizona. You know what the homeowner did? Nothing. Which is perfect!

Sometimes we will run across some baby rabbits, or seemingly “abandoned” animals such as coyotes or baby birds. Please don’t touch, engage with or otherwise harass these animals.

If you honestly feel that they need to be rescued, contact your local Game and Fish Department or local wildlife rescue. They will happily send out a qualified professional to investigate.

We know your intentions are good!

While we know how hard it is to resist a baby bobcat or coyote, or a bird that has fallen from a nest, this is not only dangerous for you but for the young animal.

The animal parents likely left their “kids” in what they deemed to be a safe location while they forage for food and water. Sometimes, it may take hours or even a day for the parent to return.

“Picking up or ‘rescuing’ baby wildlife is often unnecessary and can have negative consequences,” said Stacey Sekscienski, Arizona Game and Fish Department Wildlife Education program manager. “The mother is often left searching for her young, and baby wildlife raised by humans is less likely to survive if released back into the wild.”

Larger Orphaned Species

Wildlife should be left alone – this is especially true if you happen upon a young predator baby. Bear cubs, elk calves, or deer fawns may even have to be euthanized because it cannot be released back in the wild.

In 2016, visitors at Yellowstone Park happened upon a baby bison that looked cold and placed it into their SUV to warm up. The elk calf eventually had to be euthanized when it’s mother rejected it due to human interference.

Each year, wildlife centers are inundated with baby birds, rabbits and other wildlife that were unnecessarily taken from the wild. Zoos and other wildlife facilities have very limited holding space and even fewer volunteers available who can handle these animals.

When You Should Interfere

There are occasions when you may need to interfere. If a wild animal has been attacked and injured by a dog or cat, is clearly injured or sick, or has been hit by a car, please watch the animal from a distance while contacting your local licensed wildlife rehabilitator. This is also true if you have strong evidence that one or both parents have not been caring for the young.

Sometimes, you can help, but risk potential death by enraged mothers if you do. In 2018, a man stumbled upon an emaciated bear cub that was soaking wet and barely breathing. It would almost certainly die had he not taken action. Sometimes, the mothers of cubs will abandon their sick or injured cubs, but that doesn’t mean they want humans picking them up.

Luckily, mama bear was not seen as he trekked back to his car and rushed the cub to Turtle Ridge Wildlife Center where he was saved. But, now the question arises about the life ahead of him.

Young wildlife found in your yard or in the field is rarely abandoned. Typically, once the perceived predator (you, or your cat or dog) leaves the area, one or both parents will return and continue to care for the young.

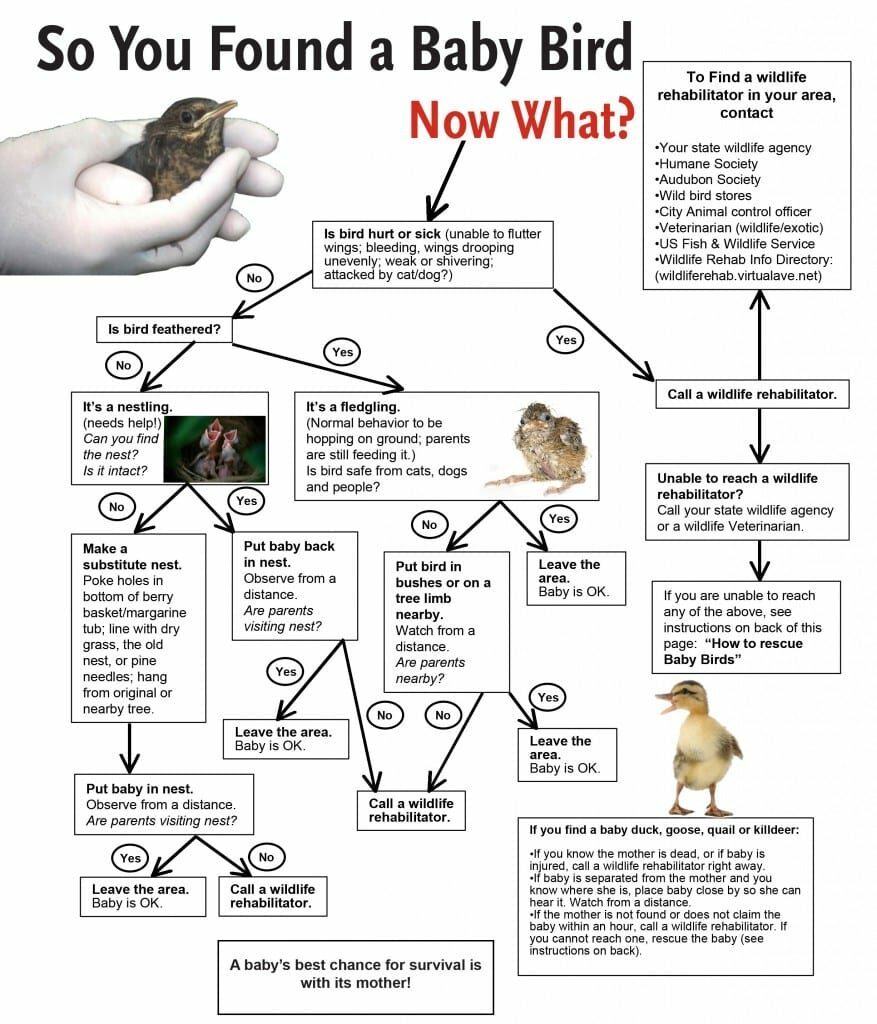

Rescuing Baby Birds

Baby birds are the most common wildlife species encountered by the public and removed from the wild. Young birds that have fallen from the nest can be placed back in the nest or as close as possible, preferably in an artificial nest. Those birds that are partially flighted should be left alone or in some cases moved nearby out of harm’s way.

Contrary to popular belief, human scent will not prevent the parents from returning to care for their young. Eggs of ground-nesting birds like quail should be left in place when discovered.

If you have questions about a specific situation, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator. These can generally be found on your state Game and Fish Department website.

If you live in Arizona, visit www.azgfd.gov/urbanwildlife for a list of resources.